Smart City Technology Abounds, but Planners Will Help Put It to Good Use

Planners occupy a critical place in the advancement of smart cities—inherently, next to the big-data informational technologies that will make these cities thrive.

Planners face challenging questions while trying to understand what existing, trending, emerging and future smart city and transportation technologies mean for sustainable and smart corridor redevelopment.

-

How should a community’s smart city vision be articulated?

-

What strategies are needed to advance from plan to action?

-

What metrics or performance indicators will define success?

-

How will “next big thing” distractions be avoided?

-

How will public trust and privacy be protected and maintained?

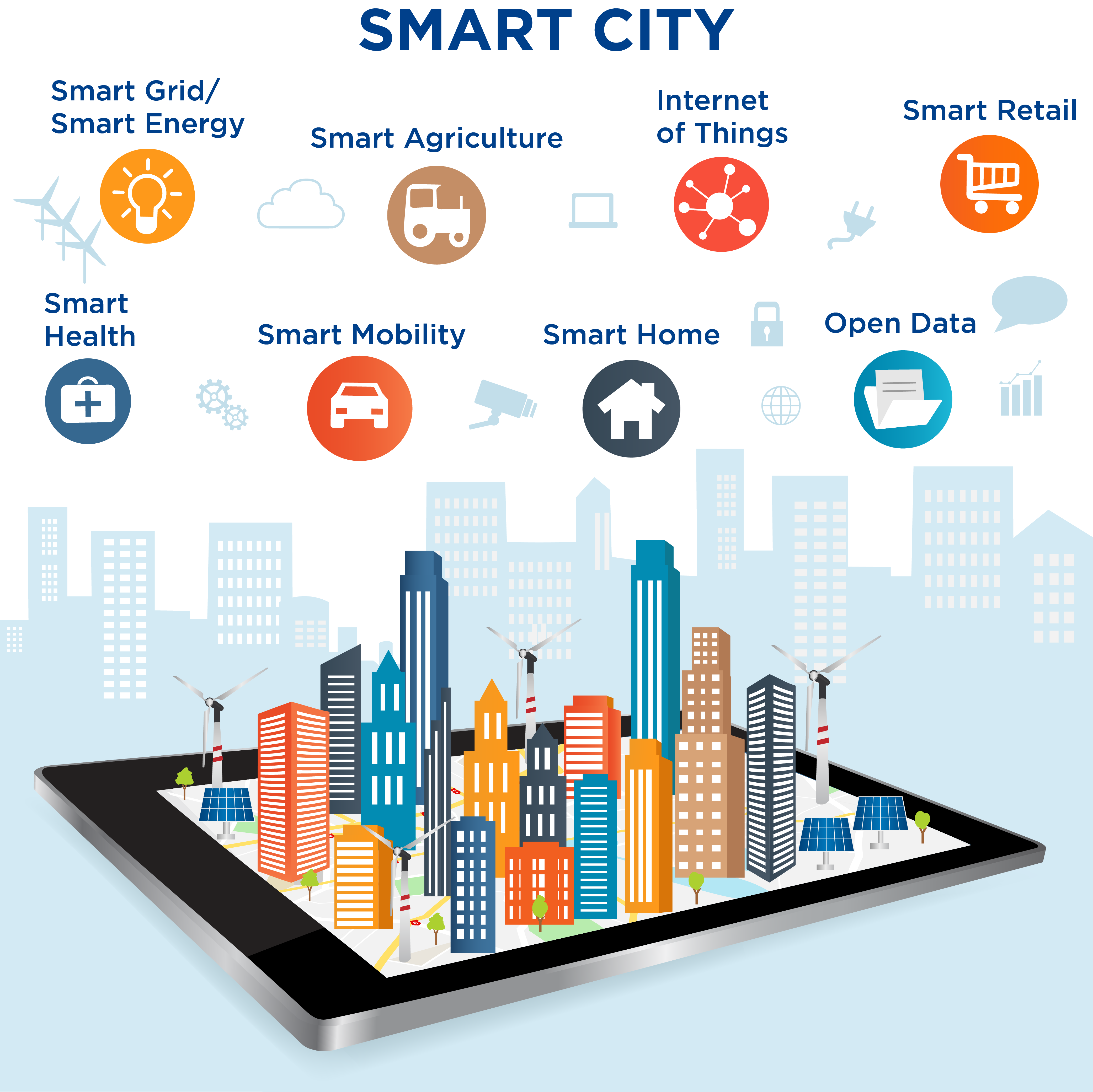

“Smart cities,” the American Planning Association says, “use information and technology to engage citizens, deliver city services and enhance urban systems. The use of smart city technologies results in cost efficiencies, resilient infrastructure and an improved urban experience.”

Buildings, roads, parking areas, energy, waste management and water/green infrastructure are urban systems that will benefit from smart city technologies. Meanwhile, social systems that stand to benefit include public safety, public health, education and our neighborhoods, to name a few.

One of the greatest challenges, naturally, is connectivity. The network of connected devices, such as vehicles, mobile phones, transportation management centers, home appliances—the internet of things—won’t function effectively without connectivity.

The planning aspect of smart city design is an evolving task—for municipalities and consultants. As was stated in an APA smart city webinar, “While technology industries are developing smart cities tools and technologies at an increasing pace, planning organizations and cities are still challenged to find effective ways of using the tools to address the public interest and respond to citizens’ needs.”

In short, will the technology bring value and improve lives?

Bike-sharing stations, such as this one in San Antonio, allow for quick trips around the city. (Shutterstock)

Smart Mobility Components

Smart mobility within corridors—linear pathways that connect places—is one of the fastest-growing components of smart city design.

Vehicle manufacturers and other heavyweight firms such as Google and Uber have spent millions in research and development to bring autonomous vehicle technology to the marketplace. Human safety and improving traffic efficiency are two primary goals. An important component is federal and state governments having policy in place to regulate the rollout of driverless cars and trucks in America—particularly to assign responsibility without limiting innovation.

Ride-sharing services and apps, of course, have been widely established over the last several years. Here are a few other examples of smart mobility initiatives:

Microtransit shuttles: Driverless shuttles are expanding to cities at various levels. They will certainly become popular in private-sector locations such as airports, hotels, college campuses and theme parks in years to come.

Bike-sharing: San Antonio’s SWell Cycle system is a bike-sharing program that allows a user to pay for usage of a bicycle in one location and return it to any other SWell Cycle station in the city because of the tracking sensors on the bike. Similar programs have been established for scooters.

Real-time scheduling: Bus and other public transit scheduling can be tracked from a smartphone, identifying arrivals and departures up to the minute. It helps users move about more efficiently.

Autonomous trucking: The growing shortage of truck drivers across the U.S. has been well-documented. Several large companies have been trial testing the operation of self-driving big rigs—some have successfully traveled up to 1,000 miles.

On-demand urban air transportation: Uber has publicly stated it plans to offer “flying car” transportation within a decade through a network of small, electric aircrafts.

Smart parking: Finding a place to park at the airport when you’re in a rush can elevate stress levels. Sensors within a smart parking system will detect whether a space is occupied and transmit data to a central server. A smartphone app will then guide a driver to the free space and manage payment on the spot.

Pothole identification: An application called Street Bump allows drivers to take photos, geolocate and report potholes around the City of Boston.

And that’s just the beginning.

Good planning will come from more than big data. It will come from those who apply critical analysis and thinking of the data to identify the right path forward and discern what is useful, what is extra and what could be harmful to our communities.

Halff is committed to shaping and revitalizing communities, as well as generating economic growth through creative and sustainable planning solutions. For more information about Halff’s Planning and Landscape Architecture practice, write to Info-Landscape@Halff.com.